Interweaving Dreams

The editorial team asked our Copenhagen-based colleague Carla Packness to pick her favorite works from the current group show "Terravision." Read our newest five-minute read, where Carla shares her thoughts on Laure Prouvost's and Emilia Bergmark's works.

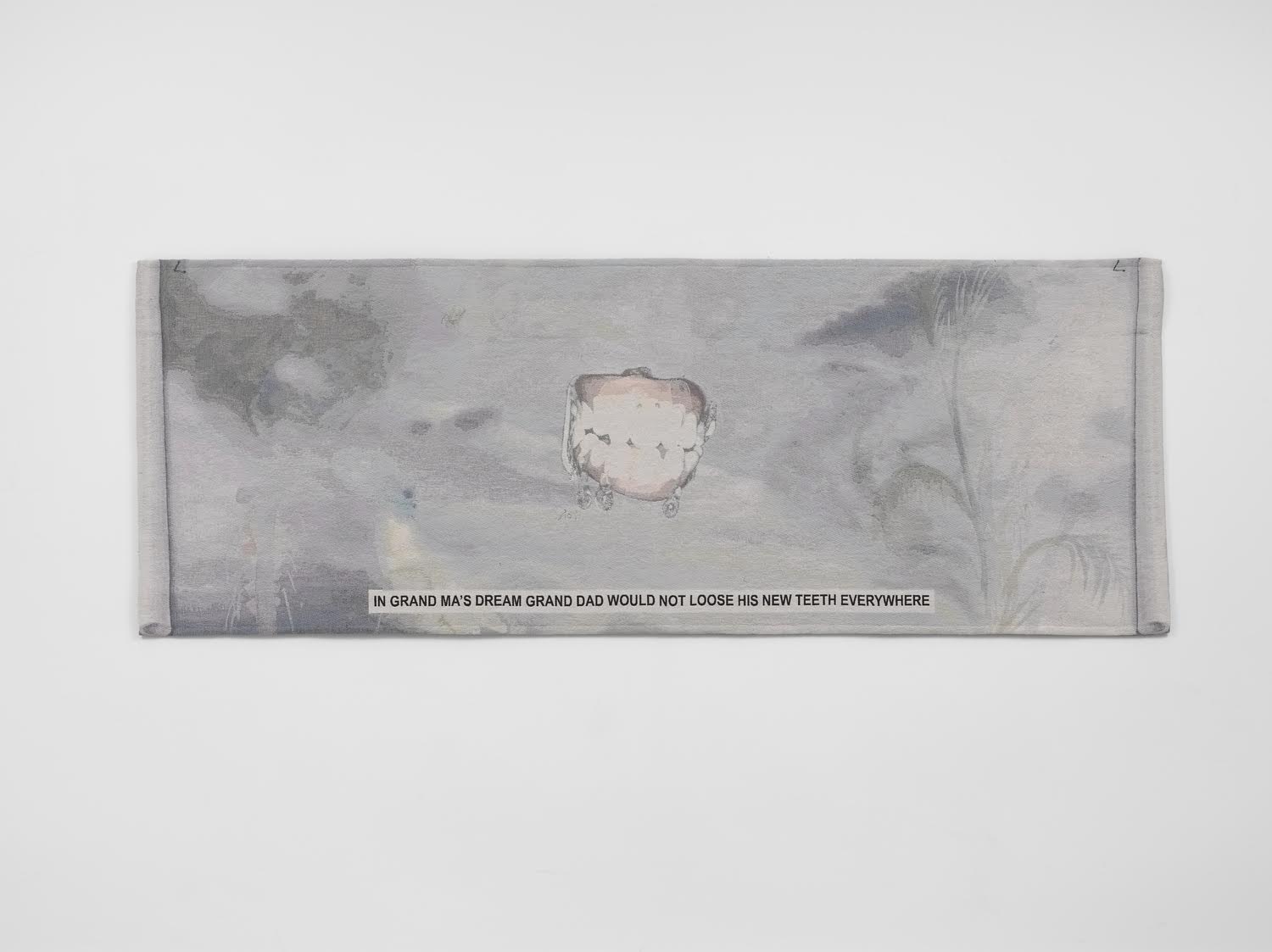

Hanging high on the wall of the Copenhagen gallery kitchen, just below the arches of the ceiling, the tapestry by Laure Prouvost unfolds like a scroll that has been rolled up for ages, thick and heavy. Its only script, which is also its title, reads: “In grand ma’s dream, grand dad would not loose his new teeth everywhere”. These teeth, grand dad’s dentures— titanium white, almost luminous, dripping with glistening saliva as if fresh out of grand dad’s mouth hover above the statement.

In its brevity, the sentence tells its own story of the passing of time – here using human life as a scale – and grapples with the roles and accessories attributed to growing older.

The word “dream” is understood here as both the imaginary realm we enter during sleep as well as aspirations for the future within the physical world. The concept of dream weaving, a practice whereby hidden aspects of our dreams during sleep are introduced into our conscious, waking reality, comes to mind in front of the tapestry.

In Grand Ma’s Dream Grand Dad Would Not Loose His New Teeth Everywhere, 2018, Tapestry

100 x 290 x 1 cm

Ed. 3 of 3 + 1 AP

To support the notion of this interweaving of imaginary dreams and future inclinations, a small detour to the video work Every Sunday, Grandma, also on display in the exhibition, is helpful. The video, which again features grandma and granddad – a recurring couple in Prouvost’s practice — shows grandma soaring through the air, doing somersaults while “touching the little seaweeds of the sky” as described by the artist’s voice narrating the film. This is a dreamlike scenario where grandma is one with nature – she flows through forests and floats above the sandy beaches, consuming all the joys, the love, the terror, and the wars — and feels lighter.

In grandma’s dreams, she is free and she is a unified part of nature, flying with the birds. Circling back to the tapestry, the memory of Prouvost’s grandparents is woven into the present, telling a story through which it is possible to imagine a different future, driven by dreams, both the cherished aspirations and the ones during sleep.

4K video

On multiple levels, Bergmark also interweaves the past and the present into her tapestry, whilst remembering the generations before her. The silk that partly makes up the fabric was passed down to the artist from her grandfather’s tailor shop. In the eighties, her mother used plants from her local environment to dye the wool also used in the making of the triptych.

The threads that make up the tapestry are simultaneously embedded with the past and stained with pigment from some of the very plants depicted in the triptych.

Bluebells, Rosehips, Veronicas and Red clover, Beetles, Fire ants, Dragonflies, and Bumble bees — these are the species of the meadow that Bergmark has known like a friend since she spent her childhood summers smelling its flowers, learning their names and inviting its insects to crawl on her hands. In Norrland’s Flora in Color, most of the flourishing life from the first panel has dispersed in the last, representing the present ecosystem of the meadow.

Norrland's Flora in Color, 2023

Tapestry triptych woven on a TC 2 loom from plant dyed wool and silk

170 x 210

Each framed panel measuring 170 x 74 cm

As a response to the current biodiversity crisis of the meadow and our world in general, Bergmark has interlaced physical remnants of lived life from the past to recreate memories from her childhood and the natural environment surrounding it. As an interweaving of countless different threads marked by history, creating a collective pattern, the technique and material of the tapestry mirror the complexity of the landscape it depicts.

Thinking with the weave offers a way to imagine a thriving meadow in the future. A weave can ripple and rip, and a meadow can wilt and perish. A severed thread can also be mended and woven anew, and wouldn’t a meadow grow into new life if given the right conditions to thrive?

When Bergmark revisits the meadow today, she thinks of the term landscape amnesia – the notion that conditions change right before our eyes, but are paid no mind because it happens over a lasting period of time. The imagery of the triptych reminds us of how things were and where we are now. Still, the idea of weaving suggests a possibility of changing the pattern towards a future transformation of our environment, allowing space for all the entanglements and complexities necessary to sustain the fabric of life.