Did you know…?

Miklos von Bartha tells the remarkable story of how a Basel drug investigation led to his favourite artwork by Auguste Herbin

by

Miklos von Bartha

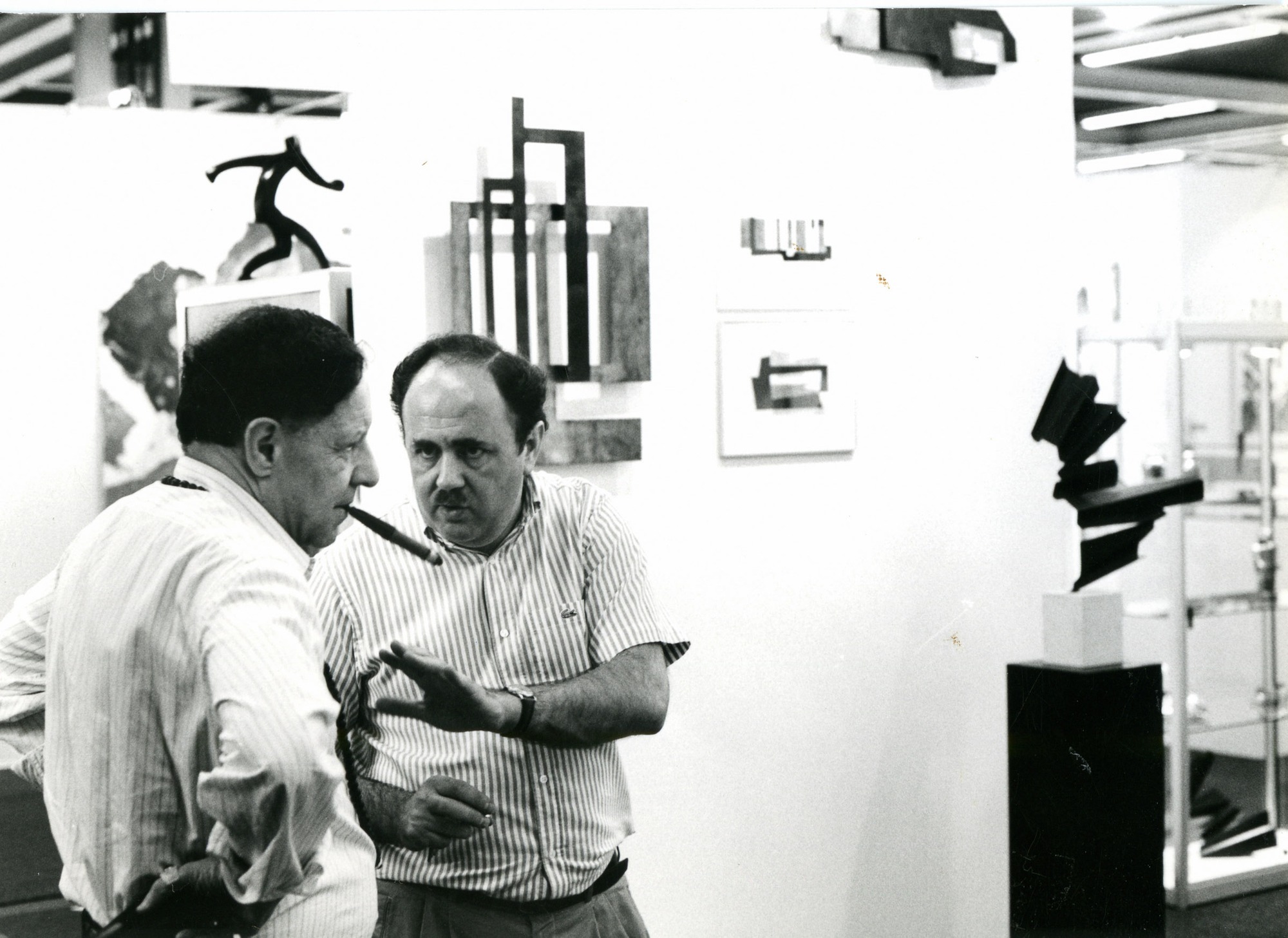

After not having heard from Carl Laszlo (the famous art dealer, collector and author, who shared a deep friendship with our founder Miklos von Bartha) for a few days, I drove to Sonnenweg. I have had a set of keys to his house for years and I have always had access. I was a little worried: he lived alone back then, and something could have happened to him.

When I arrived, I found that one of the three locks had been changed. I could not enter the house. How strange!

The next morning, when the news outlets in Basel reported the arrest of a renowned Basel art dealer, everything became clear. He was accused of drug-related offenses. That same morning, I sat across from the head of the drug squad, a bourgois politican. There were two things he was clueless about: drugs and drug addicts. As would transpire in my later conversations with him, he was not in the least suited to the tasks assigned to him.

At that time, he was still at the beginning of his career, but he would later go on to become the top Swiss drug fighter in Bern and his work would be generally highly praised, so he must have learned something in the end (and later he was also one of the best councilors Basel ever had).

I introduced myself, to which he replied that he knew me very well. His people, he assured me, had been watching me for years. I apologized to him for the unnecessary trouble I had caused him and his colleagues. The chief drug inspector (from here on ‘the CDI’) didn’t like that; it was unusual, after all, since many people around Carl were involved in the drug scene. But not me: as a sworn non-smoker and the father of two young sons, I had never even enjoyed the pleasure of smoking a joint.

Carl and I were friends, he had encouraged my wife Margareta and me to open a gallery years before. Fifty years later, I have to admit that it wasn’t a bad idea. But for the head of the drug squad it was incomprehensible that two such different people could maintain daily contact without using or exchanging drugs. He would have liked to convict me, at least as a mule. I could not help him on that front either.

‘…they both assured me that they would clearly prove to me that Carl was the criminal they had long been searching for, the person who was helping to finance the Basel drug trade’.

After our brief conversation I knew that he had no clue about his profession. He accused us of having agreed on what I would say in the event of Carl’s arrest. A drug addict—which Carl was not, by the way, later he was able to stop using cocaine from one day to the next—thought about many things, but their possible arrest was not one of them. For years we had had interesting conversations about art and artists, about the Holocaust, which he had survived, or about Hungary. The only thing we had never spoken about was what should happen after his possible arrest.

The CDI realized that he could not get out of me what he would have liked to hear. Due to my family’s experiences with the communists in post-war Hungary, nothing was more frowned upon than denunciation. And unlike many of the petty criminals in this story, who tried to save their skin by making false statements and confessions, such as a young and still unknown would-be writer, who had ratted on Carl, I was a free man who could not be charged with anything.

So he tried the friendly approach. Come on, he said, you must have taken drugs at some point. Even I, the head of the narcotics squad, smoked hashish a few times as a student. Again, I couldn’t help him. Years earlier, when the legendary Timothy Leary had offered me a line of cocaine at Sonnenweg and I politely declined, he called me bourgeois. I replied that I thought he was an asshole and that was something we both agreed on. Incidentally, after Leary’s arrest in the USA, it turned out that I was right; he squealed on friends by the dozen in order to mitigate his sentence.

So the CDI didn’t get what he wanted. He assured me that he would convict Carl. For my part, I insisted that he was totally innocent of the charges against him. We said goodbye, and he said that he would get in touch soon. He didn’t, but one of his two detectives did. He asked me to accompany him and his colleague to Sonnenweg. On the way, they both assured me that they would clearly prove to me that Carl was the criminal they had long been searching for, the person who was helping to finance the Basel drug trade. This made me inwardly furious.

One of the dealers in Basel was a nice young lady who financed her own not inconsiderable consumption with some sales. She got the funds she needed from her then lover. He, however, had no idea what she used the money for. He simply gave her a sum of cash from time to time—and I’m sure he received something in return. In my opinion, the CDI soon knew where “Snow White’s” money came from. Not from Carl, but from a very respectable, older Basel resident. He, however, was not to be charged with anything. Carl was already in custody; the unnecessary damage was already done. Some crime had to have been committed, otherwise the drug squad would be disgraced! So, off to Sonnenweg to find something.

I had to accompany the officers to testify that the two “gentlemen” didn’t do anything illegal. In my opinion, they would not have dared to do so. I, on the other hand, made off with some things in the course of several similar visits. While the other two searched the house, I sat in the lounge in Carl’s seat, in his favorite chair by Marcel Breuer, another Jewish citizen from Pécs. I soon found his bank statements, which he went through regularly. None of their business, I thought, and pocketed as many as I could. I hid the rest under a pile of books and smuggled them out over our next few visits.

After a week I received permission to visit Carl—under strict orders that we were to converse in German. We almost kept to this. A single sentence in Hungarian—for which we received a warning—and everything was discussed.

We interspersed our conversations that followed in German with every fifth or sixth word in Hungarian. In this way we were able to communicate everything to each other in key words. Carl thought it was a good thing that I had taken the papers with me. The half-dozing genius monitoring our conversation didn’t even notice.

The weeks passed. Apart from myself, there were only two ladies willing to pay Carl a visit: the legendary Jacotte von Goldschmid-Rothschild and the wonderful Ulla Dreyfuss. They, like me, had nothing to fear. And they had the necessary courage to arrange a visit, which Carl gave them great credit for, right until his death.

After a few weeks this horrific episode was over and Carl was released. Months later, at a trial, he was sentenced to a one-year suspended prison sentence for possession of cocaine and distribution to friends, but not for financing the drug trade or for trafficking, which he had initially been accused of. This way the drug squad and its leader didn’t look too bad.

I picked up Carl at Leonhardskirchplatz. He got in the car in a good mood and remarked that he had been doing damn well during the last few weeks. The provisions were excellent, regular meals three times a day, nothing like Auschwitz. Apparently, it was only the company that hadn’t been the best.

At home, on Sonnenweg, he asked me to take the wonderful Herbin portrait off the wall. “This is yours now,” he said. “You have taken such good care of me and my affairs during my absence.” It was pointless to contradict him.

To this day it is one of my favorite paintings. I hope that my sons will keep it in the family after my passing.

Miklos von Bartha

- Carl Laszlo survived a total of five concentration camps before emigrating to Basel in 1945 to live there as an art collector. His text “Ferien am Waldsee” is one of the first literary testimonies to the Holocaust and is now being reissued by the Wiener Verlag “Das vergessene Buch”. Find the short documentary on the book and László by 3sat.de here