A Voice

A special excerpt from our new anniversary book

by

Dr. David Iselin

‘We are limiting our interests to the future!’

In 1970, the antifascist resistance fighter and economist Albert O. Hirschman (1915–2012) published the book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. In this book, Hirschman, who had to flee Germany in 1933 because of his Jewish origins, develops a theory outlining possible responses from citizens and consumers to “declining quality” in government and business. In principle, there are three ways for people to react: they can exit (migrate to the competition), they can voice (express their objections), or they can react with loyalty (tacit acquiescence). Hirschman initially assumed that the greater the opportunity for exit, the less likely it was for voice to be used. In his earlier version of this “primitive model” as Hirschman called it himself there was an inverse relationship between exit and voice. E.g. if exit from a marriage by divorce is easy, less effort will be made at repairing the relationship through voice, that is, through communication and efforts at reconciliation. The later stages of the GDR caused him to adapt his own theory, for it appeared to him that the two active forms of reaction had mutually reinforced each other and helped to bring the regime down.

In 1970, a small gallery called MINIMAX opened its doors at Schützenmattstrasse 26 in Basel. One of the first exhibitions was dedicated to the Italian artist Enzo Cacciola, a key figure in the Analytical Painting movement. This was followed by exhibitions of works by the Swedish sculptor Christian Berg, the Italian sculptor, designer, and graphic artist Marcello Morandini, and the German constructivist and concrete artist Thilo Maatsch.

The Swedish and Hungarian couple Margareta and Miklos von Bartha were behind the MINIMAX gallery, having met as students at the *Schule für Gestaltung *in Basel. From the outset, they had a close relationship with the Hungarian jack-of-all-trades Carl László, who was instrumental in helping the young couple to found the gallery. László was the only one of his family to survive Auschwitz, and after the war he trained as a psychoanalyst alongside establishing an art publishing house, Panderma, and a magazine, Radar. He would become one of the most important points of contact for the von Barthas. The name MINIMAX was only used for a brief period. Since then the Gallery has simply been called von Bartha.

What happened after the initial exhibitions can be summarized in the following selective and quick-fire overview: In 1976 there was a brilliant exhibition of Hungarian avant-garde artists, including Lajos Kassák, László Perí, István Beöthy, Sándor Bortnyik, József Csáky, Lajos d’ Ebneth, Alfred Forbát, and Béla Kádár, among others. This was followed by an exhibition with the Swedish abstract painter Olle Baertling in 1978 and exhibitions with the French painter Yves Laloy, who combined figurative surrealism with an interest in complex geometric patterns. The von Barthas subsequently collaborated with and held exhibitions on eminent artists such as Imi Knoebel and Camille Graeser, as well as one on kinetic art with works by Gerhard von Graevenitz. They played a major role in the rediscovery of Arte Concreto Invencion and Arte Madí, two radical Argentinian art movements of the 1940s and 1950s. This was accompanied by museum-level publications. The gallery’s presence at major art fairs was noted—the gallery shares its fiftieth anniversary with Art Basel. In summary, the gallery has had an eventful life.

Is it possible to deduce the von Barthas’ preferences from this abbreviated list? Without wanting to overemphasize individual factors, much is “owed” to Margareta and Miklos’ graphic eye, which shows a certain inclination toward constructive, non-representational, concrete, and mostly abstract art. This is the bedrock on which the gallery has grown and continues to flourish today. The work of the second generation, Stefan (in Basel) and Niklas (in London), is also based on this to a certain extent. The sons are ensuring the continuation and expansion of the von Bartha art universe. It is a universe based on the notion of “concrete” art proposed by Theo van Doesburg in his manifesto The Basis of Concrete Painting. There is nothing, he states, “more concrete, nothing more real than a line, a color, a surface.” For the von Barthas, the line is the line, so to speak.

However, this is not a rigid attribution, it is simply a point of reference. Galerie von Bartha is also not a museum of concrete art, but a gallery. And, as is well known, galleries also sell works of art from time to time. That is why the retrospective ends here: we will turn to the present first of all, and then we must turn to the future, just as Carl László demanded in his pamphlet Panderma.

What does it mean to run a gallery today, fifty years after its foundation, and fifty years after the publication of Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, and Loyalty? It means reacting to changes in viewing and consumption habits, income and working conditions, economic, political, social and ecological conditions, as well as to a new understanding of art and new technologies. In summary: reacting to a new world.

In other words, the question is not so much how the audience behaves based on Hirschman’s options for action—do they remain loyal, raise their voices, or do they withdraw?—but rather how a gallery reacts to the audience’s altered behavior. More specifically: What can a gallery be today in order to survive in a volatile world, promote world-class art, support and protect its artists materially and intellectually, and contribute to a vibrant cultural world? Should it raise its voice, exit the art market, or accept things as they are?

The von Barthas have, from an early stage, opted to raise their voice(s). Margareta and Miklos shared the experience of “exiting” their home countries (for different reasons), and they opted for a stubborn and ongoing radical “voicitation” so to speak in their new diaspora home called Switzerland. This resistance to a status quo has been continuing to the present-day programming of the gallery. Let’s start on a microcosmic level: in 2008, the gallery launched its own print magazine, the Report right in the middle of a major media crisis. Their concept was highly diversified, to the extent that even a text by an economist like me could be published in it. To a certain degree, Report reflects the way the von Barthas see themselves in terms of their work as gallerists: they provide the vessels for artists (in the broadest sense) to communicate with the world, to make their voice heard. The gallery becomes an amplifier, a sound space.

The Report is one aspect of using voice, but what is even more important are the new architectural vessels that have been added in recent years: the new space at Kannenfeldplatz in Basel, which opened its doors in 2008, and the gallery in S-chanf. There are also initiatives such as The Imaginary Collection, an ongoing series of temporary exhibitions from the gallery’s archive, curated by independent collectors and presented in domestic spaces. The first two Collections took place at the Hotel Helvetia in Zurich in collaboration with the collector, architect, and entrepreneur Leopold Weinberg.

There are other initiatives running more quietly in the background: their important ongoing work in the secondary art market, especially for major works of concrete art, or their support for projects such as Muzeum Susch by the Polish patron Grażyna Kulczyk, which was also designed by the same architects as the Kannenfeldplatz gallery space—Stefan’s friends, Chasper Schmidlin and Lukas Voellmy.

What these examples should make clear is that we are dealing with a transdisciplinary approach, a plan of action that the von Barthas have always pursued. For example, in 1979, the legendary beatnik William S. Burroughs gave a reading in the gallery in front of one of the enigmatic “Dreamachines” that he had developed with his friend Brion Gysin. Today, there are performances e.g. by Bob and Roberta Smith at Kannenfeldplatz, and collective exhibitions realized by guest curators such as Fabian Schöneich in S-Chanf (Unterschiedswesen) or earlier by Reto Thüring, nowadays Curator of Modern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

But the gallery doesn’t only raise its voice in terms of its art; the artists currently represented by the gallery also have their own unique sound. This may be loud, like the Danish art collective Superflex. Superflex is known for placing economic, political, and social issues at the center of their work. In 2019, for example, the collective realized the exhibition *Connect With Us *at von Bartha in Basel on the topic of Bitcoin, with a sculptural installation that clearly illustrated yet simultaneously obscured the highly volatile rate of this cryptocurrency. In S-Chanf, Superflex presented the work Hospital Equipment, a work of art consisting of a set of surgical instruments that was shipped directly to Syria after the exhibition, where it became a functional element of the medical care provided during the Syrian civil war.

Or it can be a quieter moment such as when Anna Dickinson places her alchemistic glass containers, that exists beyond function, in an exhibition installation. These are works outside of time and space, in which glass galaxies and captured moments become manifest. For Dickinson, glass is not transparent or guileless, but opaque and mysterious. We could also consider the works of Landon Metz, who creates series of color field paintings that seem perfect at first glance, often through a seemingly medieval monkish style of repetition of a single subject. The appearance of these works masks a thoroughly conceptual approach, which comprises the rhythm of the production (always on the ground), the preliminary drawing, the paint’s drying process, in short, all of the preparatory work. Metz’ work, Feels So Right Now, which embodies the aforementioned principles, was hung rather unceremoniously above the visitors inside the pyramid-shaped window alcoves at Kannenfeldplatz—if that doesn’t make a statement! (Incidentally, Metz has over 19,000 followers on Instagram, to speak briefly in the language of today’s attention economy.)

Felipe Mujica’s “new” concrete art seems more formally austere. Mujica’s “installations” organize the space, subdividing it and rearranging it in a new way for the viewer. However, the works, which hang from the ceiling like posters and are often made of fabric or wood, can also be situated in a political space. This is how Mujica comes to terms with South American historical and political events, such as the military coup in Chile in the 1970s, which was a reaction to the election of Salvador Allende in the ominous year of 1970—which brings us back to our starting point.

This selection of current examples from the von Bartha artist universe clearly illustrates that art is always an act of expression, the expression of a feeling, a moment, a process. In the best-case scenario, however, this expression becomes—in Hirschman’s sense of the word—a voice: art refers to something beyond itself.

And now we take the final step and come to Carl László’s demand for the future at last. How does the gallery intend to shape the future? With a sort of radical open-mindedness. This radicalism is due to the realization that nothing remains the same and nothing can remain the same. The gallery is expanding in terms of personnel, devoting itself to a more strongly contemporary program, becoming broader, seeing itself as a vessel rather than a gallery more than ever before. New formats are being tested, such as exhibitions within exhibitions in the “cubes” at Kannenfeldplatz. Stefan’s Salon, a discussion group of five to six people, is in the planning stages. Artist productions are being expanded. This may well mean a shake-up of the gallery’s concrete “tradition,” but it is this shake-up that makes things interesting—Carl László would certainly have agreed. In this sense, a certain degree of radicalism is not just a desirable quality but an essential one. The gallery is not afraid to simply try something new. There is no master plan for the next fifty years, just an emphasis on physical space with real works of art in an age of digital immersion. It’s about coming together in one place to collectively experience that moment artists can create so well: one that changes our perspective of the world, shifts our perception, and evokes a certain feeling. For the gallery, this is both the ideal and a manifesto for the future.

This article is featured in our new anniversary publication ‘von Bartha Est. 1970’

- *‘We are limiting our interests to the future!’ *From Carl László’s magazine Panderma, March 1958: «Wir beschränken unsere Interessen auf die Zukunft!»

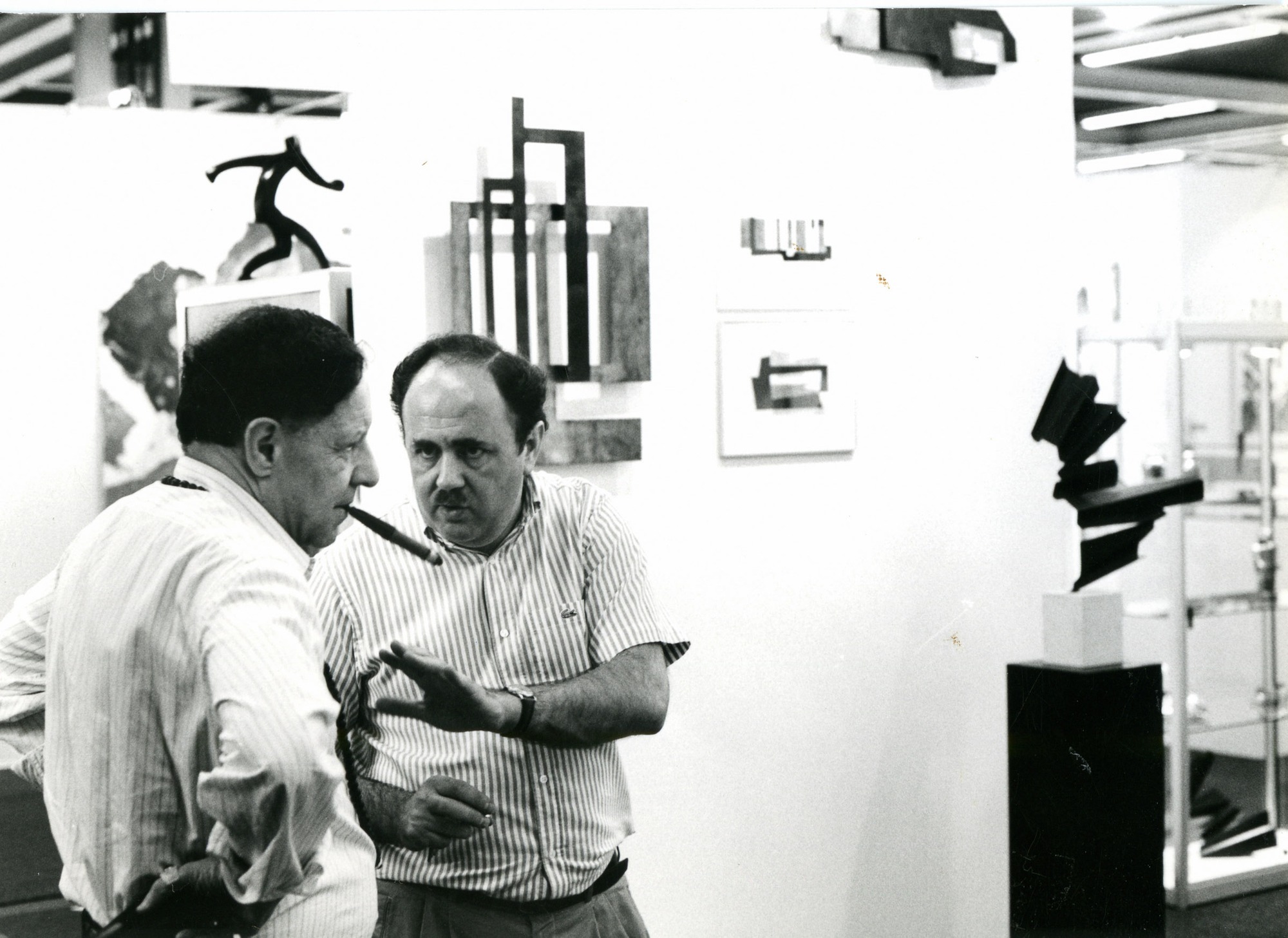

- Top image: Niklas von Bartha (brother of Stefan von Bartha) in the gallery space with works by Olle Baertling around 1979.