Toward a Cosmic Art: Anton Prinner’s Transitions

As we are treasuring beautiful works from the concrete-constructivist oeuvre of Anton Prinner, we wanted to find out more. We conducted extensive research to shed light on this enigmatic figure.

Valentina Ehnimb and Lara Holenweger are art historians and cultural producers with a focus on artistic practices informed by feminist, queer, and postcolonial theories. They studied and taught together at the Institute of Art History, University of Basel.

09.03.2024

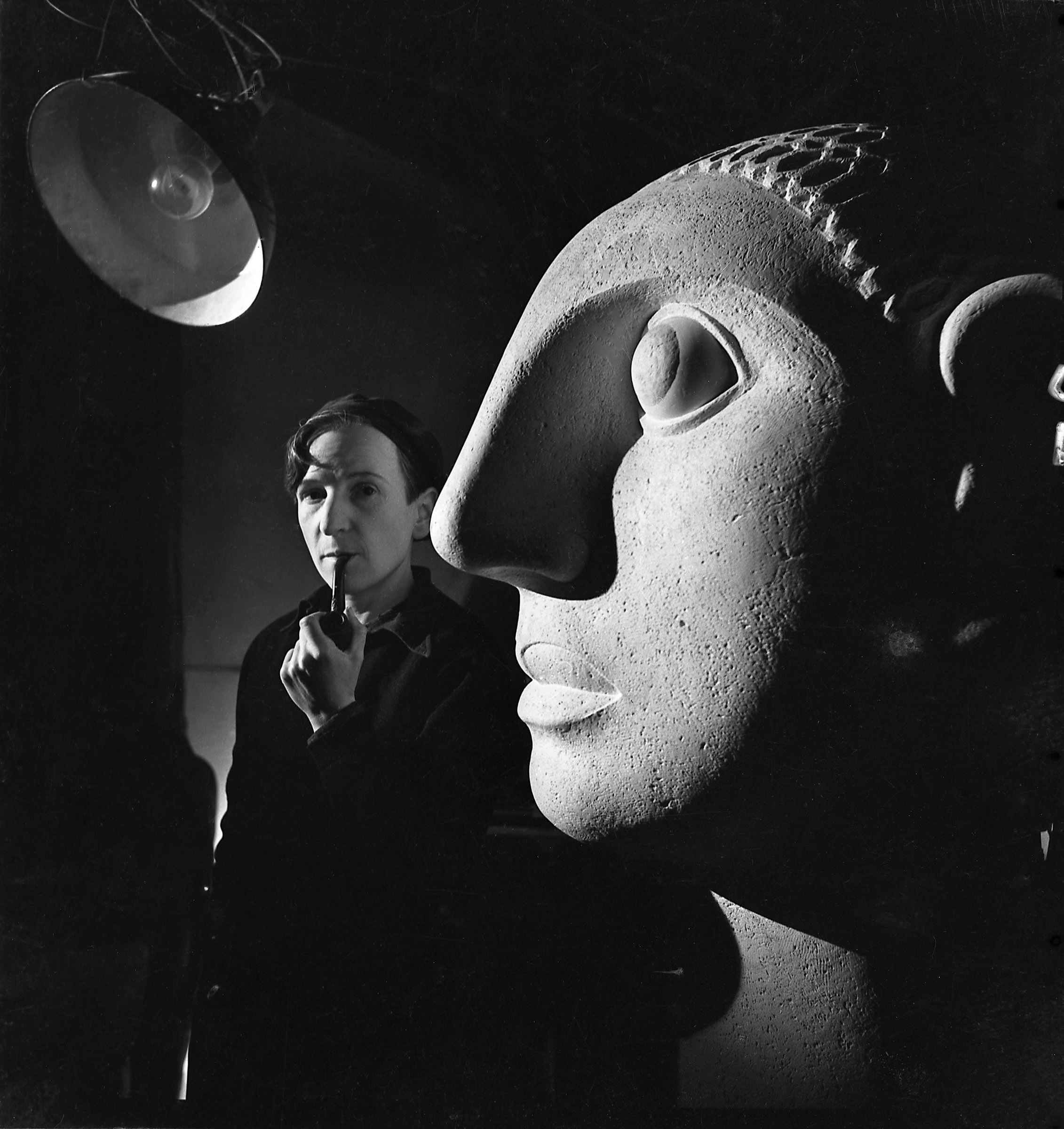

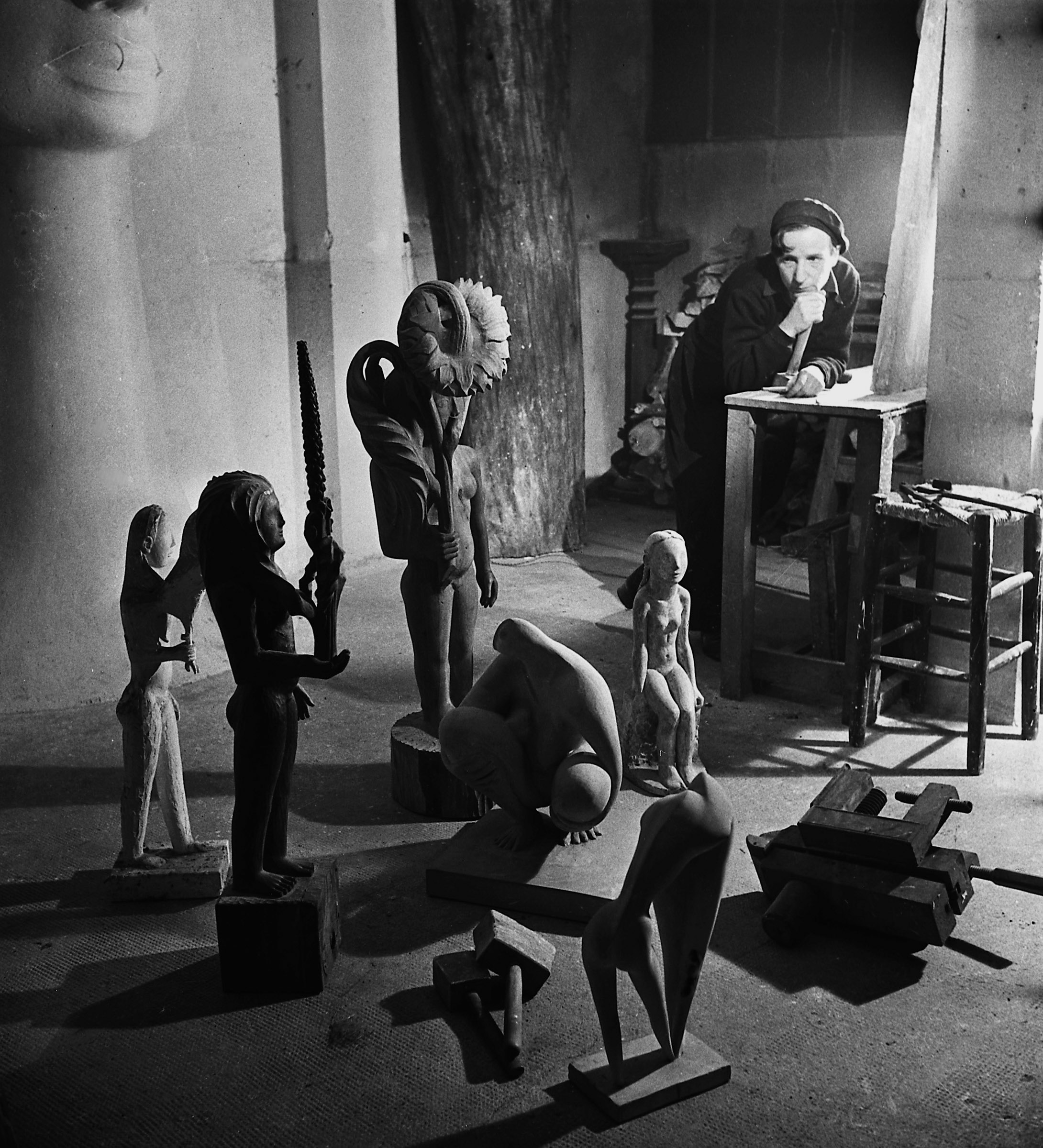

In the shadow of a giant stone sculpture, a figure appears, directing their gaze at us while pulling on a pipe. Have you heard of the artist Anton Prinner? That’s him with his artwork, titled La Femme aux grandes oreilles (1937). It takes center stage as the artist steps into the light behind his creation, suggesting a strong authorship and identification with his work.

If you want to get to know Prinner better, you have to dig deep. Primary and scientific information about the artist is not easily accessible.(1) Anecdotes of his contemporaries are rare, and his autobiographical writings are peppered with irony, jokes, and ambiguities. Speculations about his trans identity abound.(2) Although his work is well documented and preserved, it is still largely unexamined. His multifaceted oeuvre resists common labels and is driven by an urge to transcend given boundaries to explore the unknown.

Spirales Plastiques, 1935

Relief and metal on painted wood

51 x 81 x 3.5 cm

Right: Anton Prinner

Untitled, 1933

Painted wood

102 x 64 x 13 cm

Prinner was born in Budapest in 1902, where he grew up in a culturally savvy household and enjoyed many freedoms. In the 1920s, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts. He stayed in Hungary until 1927 before moving to Paris, a melting pot for artists from all over the world. Prinner then made a double move, transitioning not only geographically, from Hungary to France, but also from Anna to Anton Prinner, assuming a male attire and identity. A black beret, work clothes, and a pipe were his trademarks.(3)

During his initial years in Paris, Prinner lived in poverty and faced difficulties in making a living. Although he never returned to Hungary, he cultivated many friendships with Hungarian artists, such as Gábor Peterdi and Árpád Szenes. With the latter, Prinner painted caricatures in the nightclubs of Montmartre to make ends meet. He quickly became a prominent figure in Parisian art circles and entertained parties at his studio.(4) Prinner moved between worlds. Albeit he had many connections, he yearned for a solitary life. He frequently chose to lock himself away to work alone in his private room rather than to participate in the ongoing intellectual discussions about art in his salon.(5)

Transitions are not only present in Prinner’s biography but also in his oeuvre. He was trained as a painter, but throughout his career, he expanded and also abandoned painting, time and time again, never fixing himself: He produced a series of constructivist works, a large number of prints, and figurative, androgynous sculptures, such as the one in the photograph mentioned at the beginning. Within the variety of media, there is a shift from the abstract to the figurative (and back). These transitions could be described as a commitment to evolution, to transcending supposedly self-evident boundaries.

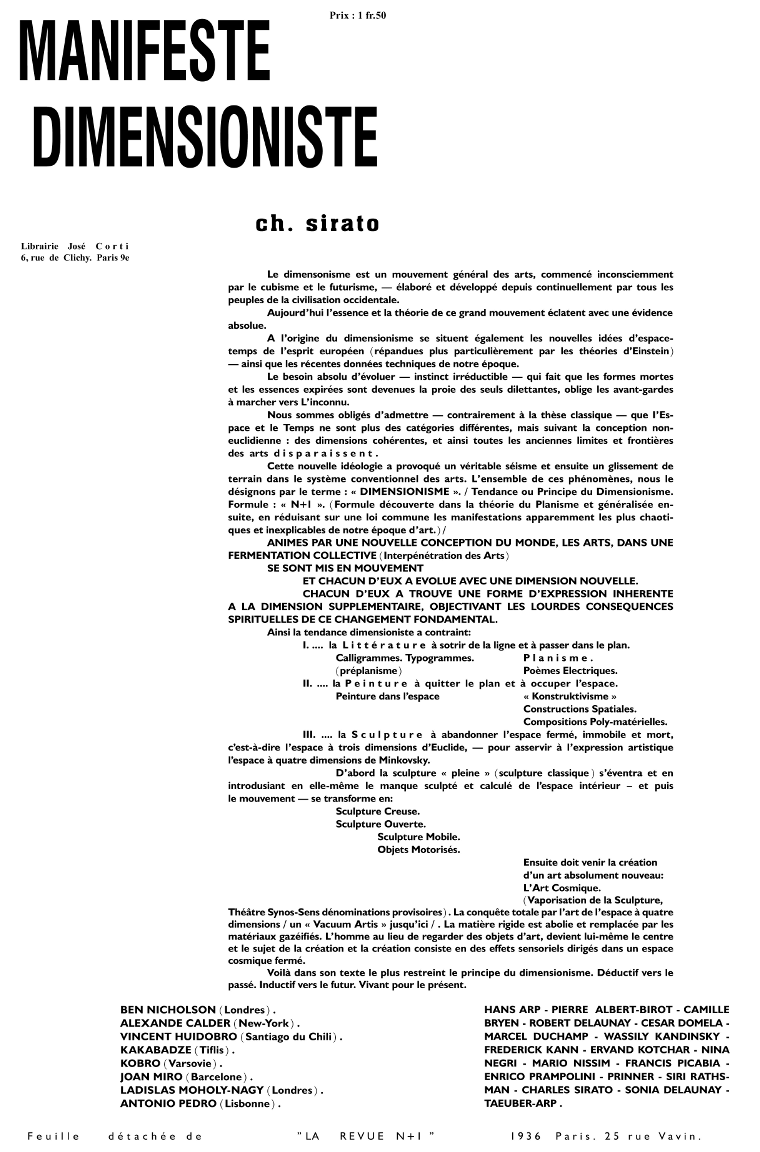

This avant-gardist urge towards evolution and transformation is clearly formulated in the Dimensionist Manifesto, which Prinner signed in 1936 – along 25 other artists, such as Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Francis Picabia, and Marcel Duchamp.(6) Starting from the revolutionary conception of space-time of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and the rapid technological development of the period, the Dimensionists declared ‘Motion’ as the new principle for all art. The transdisciplinary, universal law was embodied in the formula N+1 – every art form absorbing a “new form of expression inherent to the next dimension,” ultimately leading to a new, ‘Cosmic Art.’(7)

Error. No content found for Slider

By the time of signing the Dimensionist Manifesto, Prinner had been creating constructivist works for several years: L’Oiseau acrobate (1932) and La Colonne (1933) are examples of his search to represent an abstract universal order. Basic geometrical forms are arranged to abstract reliefs, breaking out of the two-dimensionality of the picture plane. Through optical effects of contrasting color and a composition that simultaneously seems to fold space inward and outward, these works confuse a definite spatial understanding.(8) At the same time, the titles lend different meanings to the de-constructed spaces. L’Oiseau acrobate suggests a bird opening its wings during an acrobatic flight through a blue sky, its body abstracted into triangular shapes. La Colonne on the other hand, transforms a merely functional architectural element into a body with more dimensions, into a colorful crystal-like object.

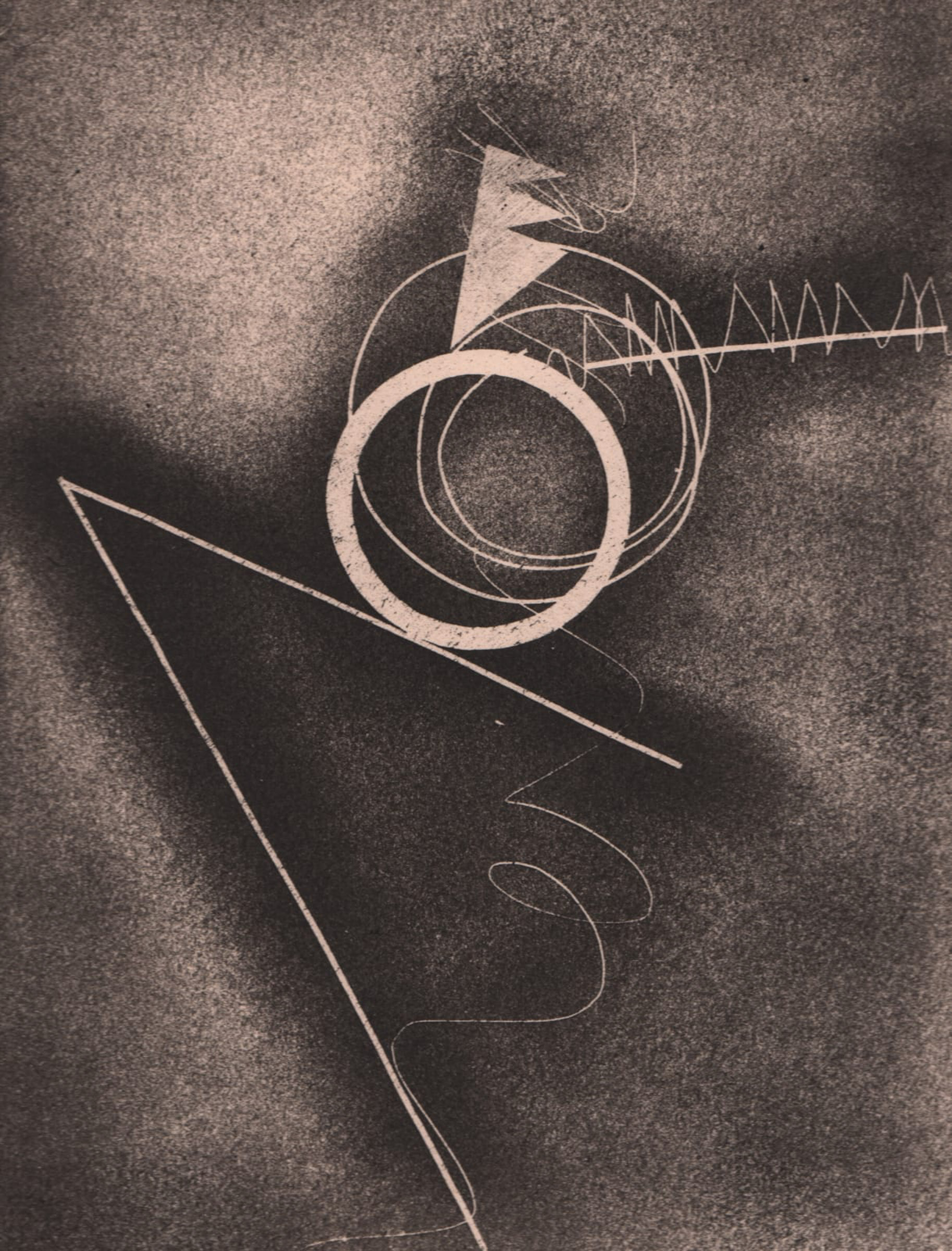

These questions continued to occupy Prinner, even while he was studying etching and printing techniques at the studio of Stanley William Hayter in 1934 and 1935. Around that time, he started to pursue this other medium with religious devotion:

“Isolated in my room, I built my boards and drew my prints, which looked like ‘signatures’ of cosmic bodies. Phenomena captured in their evolution of crystallization. […] Believing in the purity of an imaginary crystal that was to represent the universe, I constructed lines and shapes like a manic alchemist.”(9)

Prints like Problem Spiral I (1936) also reflect his inventiveness out of necessity: With copper plates being too expensive, Prinner invented a new technique, which he later named ‘Papyrogravure.’(10) He used cheap materials such as paper and cardboard, which he cut and glued together to form a relief, then covered with varnish.

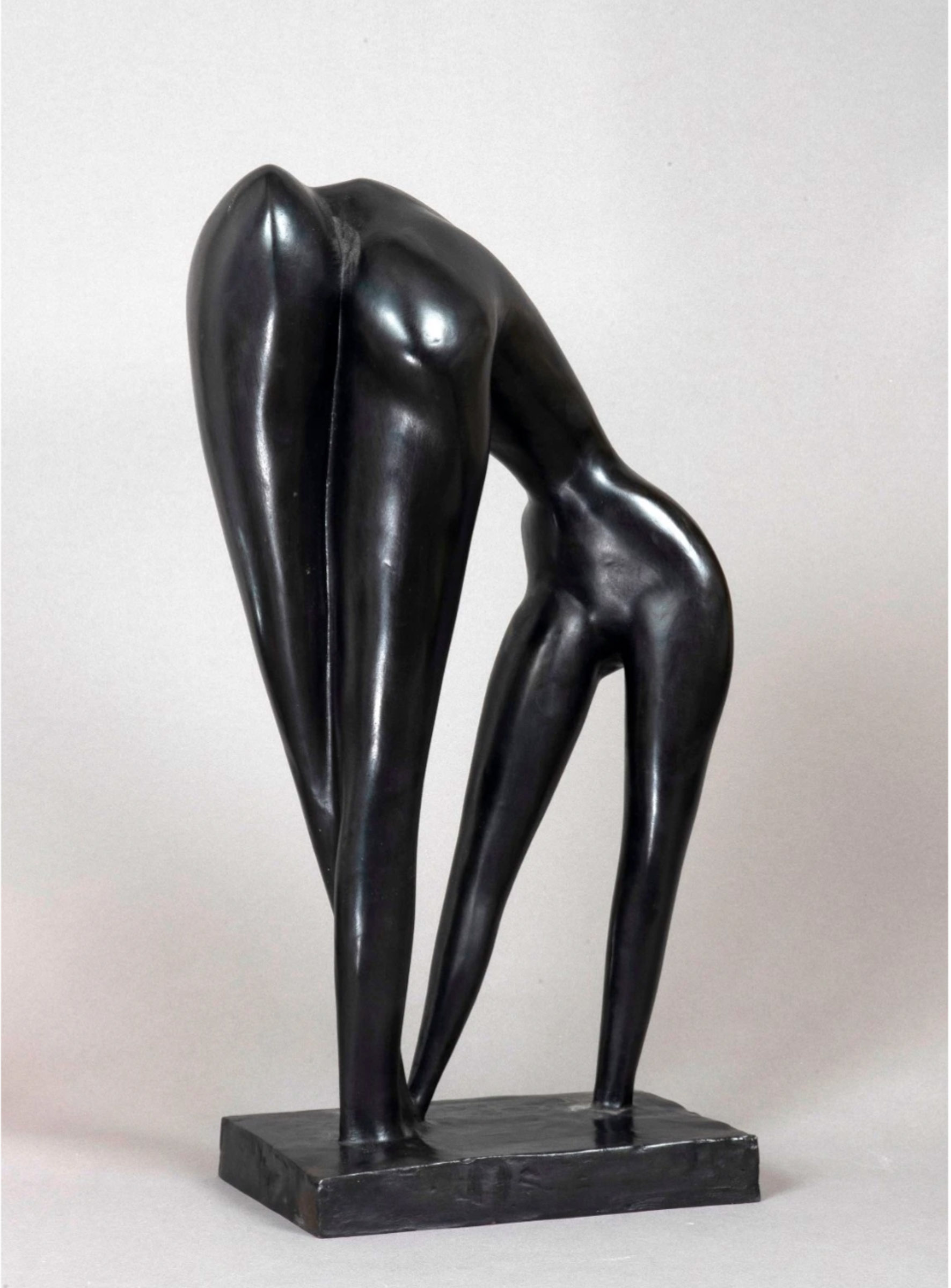

According to Prinner, he was unaware that what he was doing was ‘constructivist art’ until his friend Peterdi told him so. He describes going to constructivist exhibitions and being “disgusted.” Tired of his visions being “named, grouped, and categorized like a grocer names his cheese” by critics and contemporaries, Prinner decided to leave behind abstraction and turned to figuration—thus liberating himself from all the “isms” of his time.(11) In 1937, out of a stone block and a tree trunk, he carved two androgynous sculptures: Femme aux grandes oreilles and Double Personnage. The latter resembles two pairs of legs merging into one another. Where does a body begin? Where does it end? Is it human or more than human, a human sculpture transcending its dimensions?

Double personnage

Bronze with black patina

Sculpture, 44 cm

What seems like a radical break again is instead a continuous transition for Prinner:

“In the beginning, you look for your way. Then you change direction, swearing that the other one wasn’t the right one. Then you start to hesitate. That’s when you realize that the only way is the way that has no direction. The universal path, the goal without a goal.”(12)

Photos Émile Savitry courtesy Sophie Malexis

At the same time Prinner was working on his larger-than-life sculptures, he began to explore occult symbolism and Egyptian mythology.(13) After the war, in the late 1940s, his year-long research manifested in different series of engravings: Livre des morts des Anciens Égyptiens (1948), La Bible (1948), and La Bible ésotérique et poétique (1949). While changing idioms, learning pottery at Tapis Vert in Vallauris, and returning to painting once more throughout his later oeuvre, he remained true to his calling toward a dimensionist and ultimately cosmic art.

Untitled (Les Hublots), 1932

Wooden relief

100 x 159 x 5 cm

Prinner died in Paris in 1983. His work remained – and has yet to be acknowledged and explored deeper. It resists a common thread that holds everything together but favors connections that are more difficult to discern: Cosmic bodies that can take many shapes, the motion that becomes apparent in the transitions throughout his work. Constantly turning to new media, idioms, and materials also means opening up to the unknown: A drive towards the universal, understood as a goal without a goal, a way of embracing uncertainty.

- 1: Literary sources by Prinner, such as his autobiographical writings and letters exchanged with friends, have yet to be published and are mainly located in private collections in France and Hungary. One monograph has been published on Prinner, on the occasion of his major retrospective at the Musée de l’Abbaye Sainte-Croix des Sables d’Olonne in 2006. See: “Anton Prinner”, Exhibition Catalog Musée Sainte-Croix des Sables d’Olonne 2006–2007, Paris 2006. Also, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris houses a vast collection of prints by Prinner.

- 2: The reception of Prinner and his work raises the question about his transition: Did he transition to further his career and gain an advantage in the art market? It is known that Prinner defined himself as a homosexual man in the 1930s and that he kept his name throughout his life. But the question of why he transitioned cannot be answered conclusively. Nor is it clear whether the transition gave him any advantage. Perhaps it gave him certain freedoms. However, it can be assumed that his trans identity and queerness were also accompanied by disadvantages and the risk of being exposed to violence, especially when the Nazis occupied Paris. Furthermore, it is plausible that his trans identity and poverty contributed to his relative absence in art history and the dispersion of sources and information about his life and oeuvre. E.g. see: Júlia Cserba: The Hungarian Prinner, in: Beáta Hock et al. (Ed.): A Reader in East-Central-European Modernism 1918–1956, London 2019, S. 218–225.

- 3: Ibid., S. 218–220.

- 4: It is said that Picasso, whom Prinner met in 1942, used to call him ‘Monsieur Madame.’ While this naming can be seen as insulting from today’s perspective, their relationship still suggests a certain openness in the art scene towards queer lives. See: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/caring-for-our-collections/the-metamorphosis-of-anton-prinner (last access: December 18, 2023).

- 5: See: “LA FORÊT VIERGE AU QUATRIÈME ÉTAGE” (excerpts), in: Exhibition leaflet “Prinner 1932–35”, Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris 1965, n.p.

- 6: Charles Tamko Sirato: The Dimenionist Manifesto, in: La Revue N+1, Paris 1936, https://artpool.hu/TamkoSirato/manifeste_dimensioniste.pdf (last access: December 18, 2023).

The manifesto reads: “This absolute need to evolve, an irreducible instinct, has sent the avant-garde on their way toward the unknown […]. We must accept – contrary to the classical conception – that Space and Time are no longer separate categories, but rather that they are related dimensions in the sense of the non-Euclidean conception, and thus all the old limits and boundaries of the arts disappear.” - 7: Ibid.

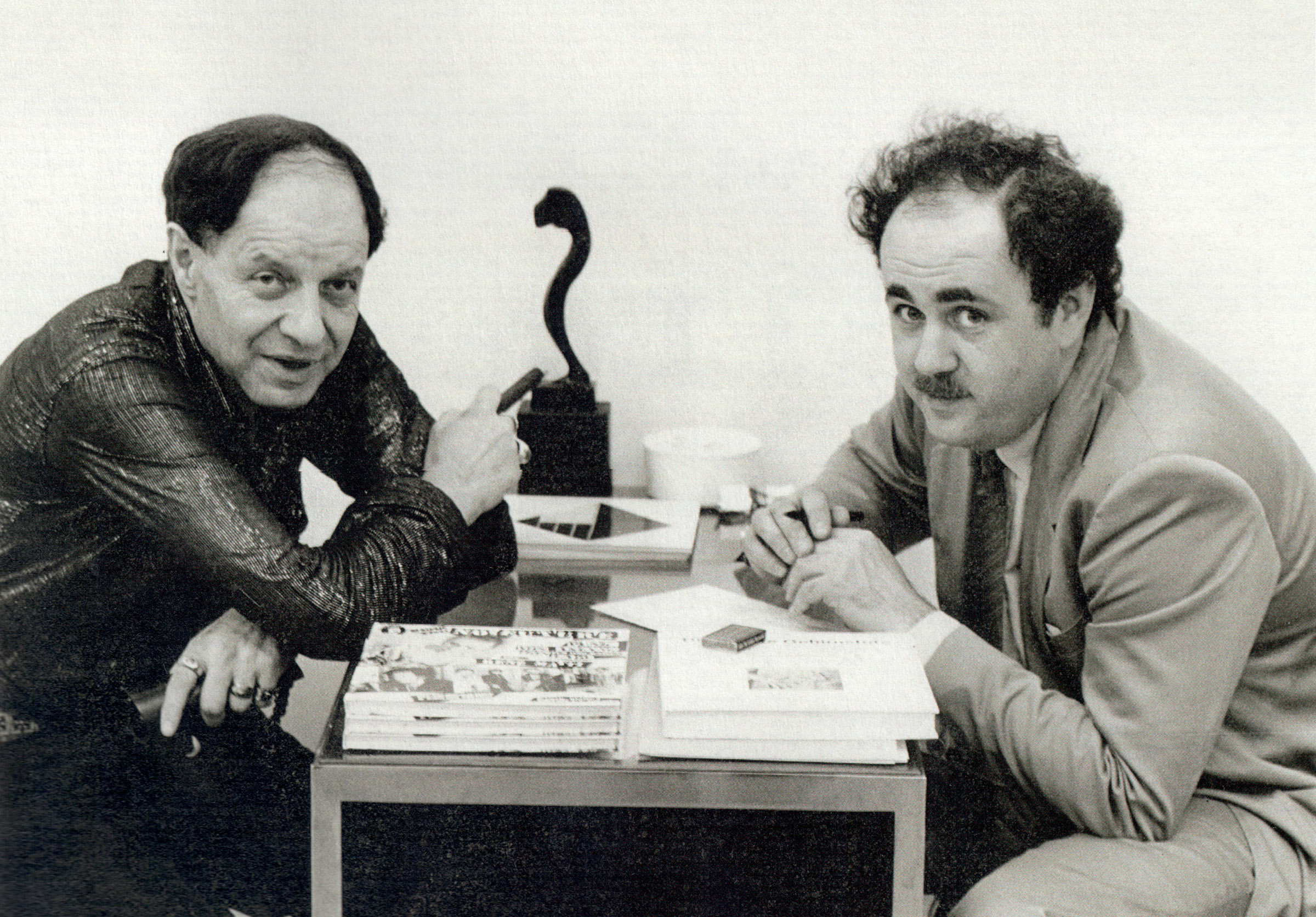

- 8: His constructivist works gained Prinner considerable admiration and connections with gallerists such as Pierre Loeb and Jeanne Bucher. In 1965, Miklos von Bartha attended a show by Prinner at Galerie Yvon Lambert, where he met the artist and bought several works. Many of these pieces can be viewed at the von Bartha gallery in Basel.

- 9: “Isolé dans ma chambre, je construisis mes planches et tirais mes épreuves qui ressemblaient à des «signatures» de corps cosmiques. Des phénomènes saisis dans leur évolution de cristallisation. […] Croyant en la pureté d’un cristal imaginaire qui devait représenter l’univers, je construisais des lignes et des formes, comme un alchimiste maniaque.” (Prinner 1932–35, n.p.).

- 10: Ibid.

- 11: Ibid.

- 12: “Au commencement, on cherche sa voie. Puis on change de direction, jurant que l’autre n’était pas la bonne. Ensuite, on commence à hésiter. A ce moment, on comprend que la seule voie est celle qui n’a pas de direction. La voie universelle, le but sans but.” (Ibid).

- 13: From 1937, Prinner shared a flat with Egyptologist Mária Peterdi, the sister of his good friend Gábor Peterdi, who fled Paris because of the Nazi occupation and later wrote texts on Prinner. See: Cserba 2019, p. 222.