A long story of very personal decisions

Stefan von Bartha talks about being the second generation to run a gallery, and a childhood spent around art and ‘crazy characters’, in a special excerpt from our anniversary book

On the occasion of von Bartha’s 50th anniversary, art historian and curator Gesine Borcherdt spoke to von Bartha’s Director, Stefan von Bartha, discussing growing up surrounded by art, in a family home which evolved to become a renowned gallery – for the Basel community, and then internationally. For Stefan, the conversation was also an opportunity to explore the impact of his parents’ work on his relationships to artists, and his plans for the gallery’s future.

Gesine Borcherdt: Mr. von Bartha, you were born in 1981 and your parents founded the gallery eleven years before you were born—exactly 50 years ago. What’s your earliest memory of living with art?Stefan von Bartha: It’s mainly the moments with the artists. I still remember when we visited Yves Laloy in Paris. I was very young at the time. He had a small room in the back of his wife’s antique shop where all his paintings were. He was sitting there and there was coffee. Laloy was incredibly fascinating to me as a child. All the crazy painted images, the heads and the geometric patterns… Also, openings were always great because there were suddenly so many people in our house, including some crazy characters. We lived in the same building as the gallery, so it felt like I really grew up in the midst of it. Just before I was born, my parents had bought a pretty run-down urban villa. It was a rather big house that they renovated step by step. On the ground floor, there was the gallery of about a hundred square meters. On the first floor was my parents’ bedroom, a large salon, and a small room with a fireplace. Guests were always welcomed there for coffee and cake. My father had a standard saying, which he would always use: “Coffee, tea, or alcohol?” My mother still lives in that building to this day. If you look at it now, it’s very elegant, neat, and clean. It was also like that back in those days—my parents are aesthetes and had furnished everything accordingly, but in those early days it was more low budget. When they first moved in, they didn’t know how to handle such a big home. But it was also during that same period which the gallery started getting more elegant and ambitious.

What was it like before?The gallery was founded in 1970. My parents met in the graphics class at what is now the Schule für Gestaltung in Basel. It was very well known at the time because Armin Hofmann, among others, was teaching there. My parents fell in love, got married, and decided to start their careers at a graphic design office. Swiss graphic design was already world class in the 70s. Just about every major logo came from Swiss design offices. It was Carl Laszlo—a collector whose living room practically birthed Art Basel—who then told my parents, “Why don’t you do art dealing? I have a large collection (or an “accumulation” as he called it because he liked the term better), I deal in it myself, but you can also deal in my inventory.” Thus, they decided to start a gallery in 1970 and found a space on Schützenmattstrasse. In the beginning, the gallery was mostly oriented toward editioned graphic works and drew on influences from Hungary, where my father is from, and Sweden, where my mother was born. In 1978 it turned into a “real” gallery since it had its own solo stand at Art Basel for the first time. Although the gallery had participated since 1970, until then it usually shared the stand with László. But now it had established itself independently. Around 1989, the gallery became truly international when my parents rediscovered the artist group Arte Concreto / Arte Madí from Buenos Aires. It was a group of artists who were strongly influenced by the Zurich concretists. It caused a furore in intellectual art circles at the time but wasn’t an immediate commercial success. My parents had bought 186 paintings in Buenos Aires directly from the artists’ studios. I still remember when those paintings were delivered to Basel because the investment meant we were technically broke. But that would change soon; a lot of people paid attention to those works. Ella Fontanals -Cisneros’ donation to the New York MoMA, for example, included many works by artists whose career revival started in Europe with my parents’ decision to take this risk. Their works are now in important collections, from the Centre Pompidou to the Guggenheim Museum. So that was a big breakthrough for the gallery’s reputation.

un nain credule

Oil on canvas

60 cm x 46 cm

The gallery has always combined contemporary art with classical art dealing, for example exhibitions with artists like Enzo Cacciola, Janos Fajo, Thilo Maatsch, or Marcello Morandini. Over the years, this increasingly meant showing established contemporary art in dialogue with modern art. In 2007 my parents opened the branch in the Engadin, and in 2008 there was the new Basel space at Kannenfeldplatz, where I took charge of the contemporary program. After about 30 years in my parents’ building on Schertlingasse, the gallery was then moved altogether to Kannenfeldplatz. We expanded the space and brought everything with us: the library, offices, archives, etc. The plan is to continue working in an international context from here. But we’re also very proud of our history. Especially because all the time the motivation behind the gallery has always been more personal than commercial. Now, when we’re working through the archives, we sometimes ask ourselves “what were we thinking back then?” (laughs). Everything was determined by friendships and fascination—you can still feel all the life and energy that went into the gallery very strongly. But now that I’m the second generation, the goal is to build on this foundation by bringing in new contemporary positions as well as historical ones. The gallery should continue to grow while maintaining its fierce commitment.

Was it always clear to you that you wanted to work in the gallery?Well, when I was eighteen I wanted to sell vintage design. But I quickly realized that I was more into collecting it than selling it. Then I had a brief crisis where I didn’t really know which direction to take. But then—and this sounds a bit sentimental—I had a key moment at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Mentally I wasn’t doing so well at the time, but standing in the museum I suddenly felt very comfortable and felt that art was something I understood a lot about. I later worked at Nordenhake in Berlin and then built up the gallery here at Kannenfeldplatz. At the beginning, I completely overestimated myself. But I learned a lot from the artists: a process that will always continue. Everyone has certain uncertainties. But when I’m in the gallery or in a studio, those are the moments when I feel I am my true self, here I am comfortable, at ease and also focussed. Thus, the only logical conclusion was for me to live out that passion.

And only from this feeling can one move forward confidently.Yes, you keep asking yourself “what am I doing” and having very critical discussions with the gallery’s artists. That’s a lot of what keeps me going today. I used to be the kind of person who would easily snap or feel provoked if someone questioned what I was doing. Today, I’m interested in criticism, and I want to know exactly what we’re doing wrong, what we can improve, or what people would like more of. Today, having conversations about these things are essential for me.

Yes, I don’t think the model of a program gallery has much of a future. It gets boring at some point. One of the biggest goals right now is to move past that reputation. We’re currently struggling with the fact that people always position us in terms of concrete art or kinetics. Of course, this has to do with our history, and also because the gallery has been very successful here. We’ve definitely benefited from the hype around kinetic art that arose about 10 years ago, when there was a Zero exhibition opening somewhere every week. We had lots of loans out everywhere, which put Bartha’s name in that corner. Now we’re trying to get out of it. Positions like Landon Metz, Sarah Oppenheimer, Christian Andersson, Superflex are therefore very important. We want even more artists like that, but also to let things grow organically.

But the tendency toward conceptual positions remains?Yes, the works of many artists have a geometric composition as their first impulse. And, of course, you either like this kind of visual rigour or you don’t. But work like Marianne Eigenheer’s, for example, has something very poetic about it. We’d like to show something like that much more, but it’s something we have to work toward. Certainly we have to be more courageous… The sentence that drives us at the moment is from Daniel Robert Hunziker: “The moment you lose your comfort zone it’s getting interesting.” Our anniversary exhibition will therefore show historical positions, but we will of course also bring in some new energy with contemporary artists. I think next year’s exhibition agenda will surprise a lot of people.

Can you describe the moment when an artwork captivates you—the moment that makes you want to know more and maybe even exhibit the artist?A lot of times, it’s happened that I don’t immediately understand the works that appeal to me the most. I often put them aside for the time being. Then, when I see them again and get to know the artist personally, I find out if there’s something really going on. Landon Metz is a great example. Our former gallery director Philipp Zollinger pointed him out to me. I liked his work very much and I bought a piece. But I wasn’t quite there with it just yet. Then I observed him for half a year and read a lot about him—that’s really important for me: to learn a lot about the work, the working method, and the ideas. Then I got to know him personally, and things took on a completely different dynamic. On collaborating with artists, just before I start working with them, there’s one very key step, and it has nothing to do with the work as such: I have dinner with the artist. We talk and spend time together. That way I can get a sense of how a person behaves and whether the motivation is mutual. That’s when I get to the point of effectively striving toward a collaboration.

So, it’s important to be close to the artists? I’m asking because that’s not the case with all gallerists. Some only know a few of the artists in their program personally, and they don’t even get along with the others particularly well.I can only work with people that I also get along with personally. We don’t have a single artist in our program who’s only there because they provide a certain security. I adhere very strictly to a beautiful sentence by Bruno Bischofberger, who once said, “I became a gallery owner so that I could afford to collect.” That’s how I see it, too. I find the conversations with the artists in their studios most exciting, followed afterwards by what we can then realize together. And the third step is to be able to own their works ourselves. That’s what drives me the most. For example, two years ago, when Imi Knoebel’s exhibition was being installed at Haus Konstruktiv, I saw a completely new work by him. That made me really nervous. The next day, I went to the museum again. Carmen Knoebel was there, and I couldn’t wait to talk to her about that work, and whether I could buy it for my collection. Which was complete nonsense at the time, because I was ruining myself privately. But I thought it was such an incredibly good painting! Now it’s hanging in our living room, and it’s incredible to own it. So, it’s not about the financial value of the work, but about what it can mean to me personally.

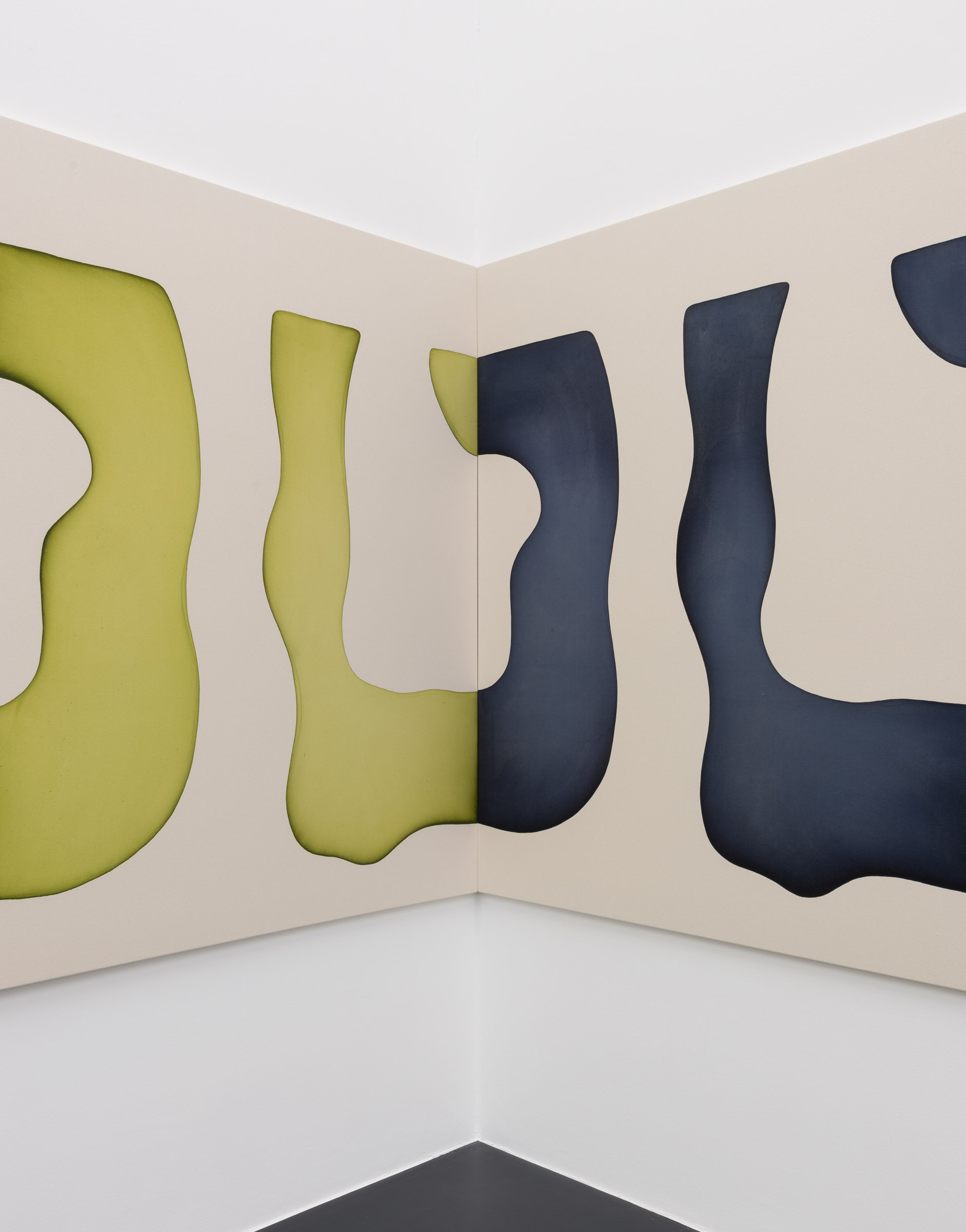

Fourth Wall, 2018

Exhibition view

von Bartha, S-chanf

Estructura sobre fondo amarillo, 1950

Oil on canvas

55×45cm

Yes, there is. It’s curated by Beat Wismer. And it’s not called an anniversary exhibition, we don’t use the age “50 years” anywhere—I think that’s too old-fashioned. The exhibition is called The Backward Glance can be a Glimpse into the Future and opens in September 2020. We’ll be showing a lot of work from the program, but also four or five positions for the future. We want to show where we’ve come from, what we’re doing today, and where the journey will take us. In August we’ll be showing our first exhibition with Claudia Wieser in the Engadin. In November Imi Knoebel and Bernar Venet will follow in Basel. And in December we bring John Wood & Paul Harrison to the Engadin.

Will art fairs continue to be important for you, especially in the quantity that we’ve seen recently?I think things will change a lot. You can already sense a certain fatigue. I feel like 10 to 15 years ago the fairs were a bit more rock and roll. Take, for example, the exhibition Fourteen Rooms at Art Basel 2014, where 14 solo presentations were shown in 14 separate rooms —a great concept! I’d like to see more things like that again. But the fault lies mainly with the exhibitors. Often, they only want to show the eye-catchers—we do too sometimes, I wouldn’t count myself as an exception. But what annoys me most is the attitude. The gallerists often leave after just one or two days. Then there’s just a half-motivated crew sitting there, in the worst case hungover from the night before, typing away on their smartphones. I think the great danger of the fairs—and here I’d say that I am an exception—lies in the fact that the galleries only focus on big collectors, visitors with money, or friends. They completely forget that there are people out there who visit fairs on the weekend or buy artworks for 10,000 CHF or less.

Sounds like you’ve learned from your mistakes…I once was invited by one of my biggest collectors in New York in an incredibly elegant café on Madison Avenue. Shortly before, I’d gotten a bit annoyed by a friend on the phone because he was asking me for what must have been the tenth time if he should now buy a particular painting for 30,000 CHF. He had never bought a painting before and said that this was already a lot of money. And so I ran into this café and the collector was sitting there, a very close friend of the family, and asked “What’s up?” I explained it to him… Then he tore me apart. And rightly so! He said “when you spend 30,000 CHF on something, you have to know what it’s for.” Since then I’ve been telling myself that even if someone only buys something for 1000 CHF, it’s our job to inform them about the work! We all really need to get over this widespread arrogance, thinking we’re too big for that. You can’t just focus only selling a single 100,000 CHF painting. The best things usually come from an apparently small exchange!